The global aquaculture industry, which now supplies over half of the world’s seafood, is powered by a single, critical input: formulated feed.fish food making machine For farmed salmon, shrimp, tilapia, and seabass, the pellets they are fed are not simple ground-up fish. They are the product of sophisticated, industrial-scale engineering designed to optimize growth, control cost, and manage environmental impact. Here’s what happens inside the aquafeed factory.

1. The Raw Material Paradox: Saving the Oceans by Using Them Differently

The core challenge of modern aquafeed is replacing the historical cornerstone: wild-caught fishmeal and fish oil. Early feeds relied heavily on these ingredients, leading to criticism of “fishing down the food chain” to feed captive fish.

- The New Recipe: Today’s feed is a complex blend. While high-value species like salmon still require significant fish oil for essential omega-3s (EPA/DHA), the protein base has dramatically shifted. A typical formulation now includes:

- Alternative Proteins: Soybean meal, corn gluten, poultry by-product meal, feather meal, and insect meal.

- Alternative Fats: Algal oils (a sustainable source of DHA), canola oil, and poultry fat.

- Specialized Additives: Binders, synthetic amino acids (like lysine and methionine), vitamins, minerals, and pigments.

The Industry’s Claim: This shift reduces pressure on forage fish stocks. fish food making machine The reality is more nuanced: for some species, replacement is highly successful; for others, like marine carnivores, the need for marine-derived nutrients remains a significant sustainability hurdle.

2. The High-Stakes Cooking Process: Extrusion

The transformation of this powder blend into a water-stable pellet is where the engineering shines. The dominant technology is twin-screw steam extrusion, a more advanced cousin of the process used for pet food.

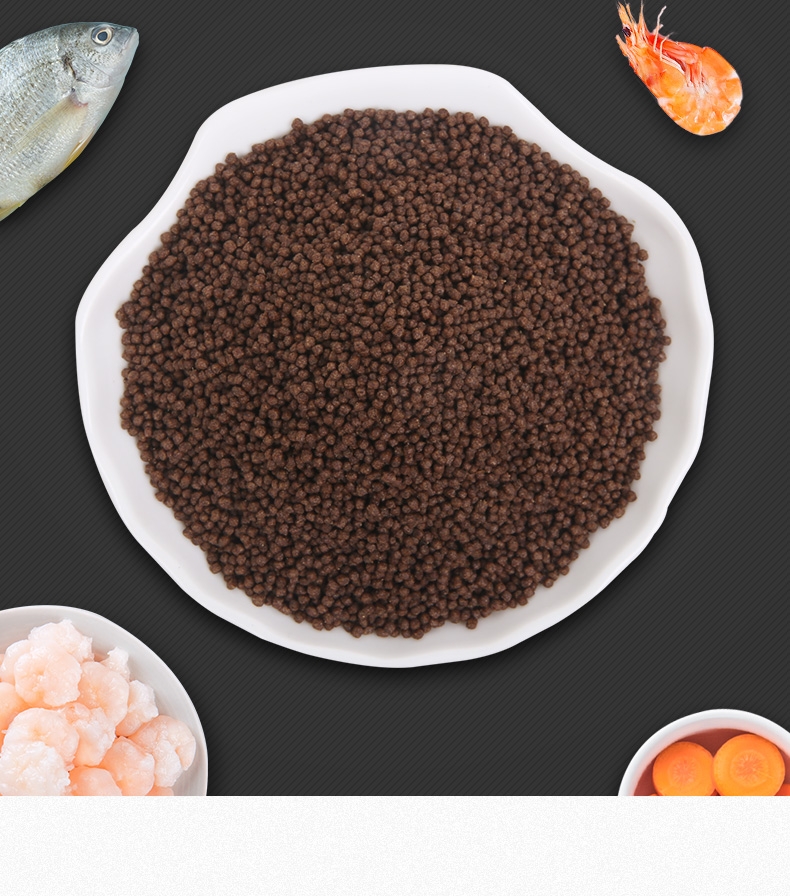

- Step 1: Superfine Grinding & Mixing – All ingredients are ground into an ultra-fine powder and blended with extreme precision to ensure every micro-pellet contains the exact nutrient profile.

- Step 2: Conditioning & Cooking – The mix enters a preconditioner where steam is injected, beginning the starch gelatinization process. It then moves into the extruder barrel. Here, under intense pressure, heat (from friction and steam), and mechanical shear, fish food making machine the mixture is fully cooked. This process:

- Gelatinizes starches, making them digestible and acting as a natural binder.

- Denatures proteins, improving digestibility.

- Kills pathogens like Salmonella.

- Step 3: Shaping & Drying – The hot, plasticized dough is forced through a die, creating long strands that are cut into pellets. The key difference from pet food extrusion is the need for water stability. The pellets then enter massive, multi-stage dryers (often fluidized bed dryers) to reduce moisture to below 10%, ensuring they don’t disintegrate immediately in water.

- Step 4: The Vital Coating (Post-Pelleting Liquid Application – PPL) – After drying, the porous pellets enter a vacuum coater. A vacuum is drawn to remove air from the pores, then liquid nutrients—primarily fish oil or algal oil—are added. The vacuum is released, forcing the precious oils deep into the pellet’s core. This protects the oils from oxidizing in the water and ensures the fish consume them.

3. The Hidden Ingredients: What’s Really in the Pellet?

Beyond macronutrients, modern feeds contain a suite of additives critical for animal health, farmer economics, and even consumer appeal.

- Pigments (for Salmon and Trout): Wild salmon get their pink flesh from eating crustaceans like krill. Farmed salmon achieve this through added carotenoids, primarily astaxanthin, which is synthesized industrially or derived from yeast or algae. Without it, their flesh would be gray.

- Binders: Polymers like guar gum or wheat gluten are used to ensure the pellet holds together in water, minimizing nutrient leaching and water pollution.

- Health Supplements: Probiotics, prebiotics, and immunostimulants (like beta-glucans) are increasingly added to boost gut health and disease resistance, reducing the need for antibiotics.

- Antioxidants: Added to the oil and feed to prevent rancidity during storage.

4. The Environmental and Ethical Catch

The processing is efficient, but the system faces major critiques:

- Ingredient Sourcing: While reducing fishmeal use is positive, the shift to terrestrial crops like soy links aquaculture to deforestation and land-use change. The sustainability of poultry by-products is also debated.

- Nutrient Pollution: Despite water-stable pellets, uneaten feed and fish waste contribute to nutrient loading in surrounding waters, potentially causing eutrophication.

- The Long Supply Chain: The carbon footprint of a feed containing Peruvian fishmeal, Brazilian soy, European wheat gluten, and algal oil from the US, shipped to a farm in Vietnam, is colossal and often uncalculated.

Industrial aquafeed is a marvel of nutritional science and food engineering, allowing us to farm fish at scale. It is a primary reason aquaculture has grown so rapidly. However, it also represents a fundamental disconnection—turning fish, which evolved to eat specific diets in the wild, into recipients of a globalized, land-sea hybrid formula.

The true “revelation” is not a sinister secret, but a complex trade-off. The process saves wild fish stocks from higher pressure but ties the health of our oceans to global commodity agriculture. fish food making machine The future of feed lies in closing this loop: scaling up truly sustainable ingredients like insect meal, single-cell proteins, and advanced algal oils to create a circular system that no longer competes with terrestrial agriculture or wild ecosystems. Until then, every farmed fish pellet is a tiny, engineered symbol of our struggle to feed the planet while protecting its resources.